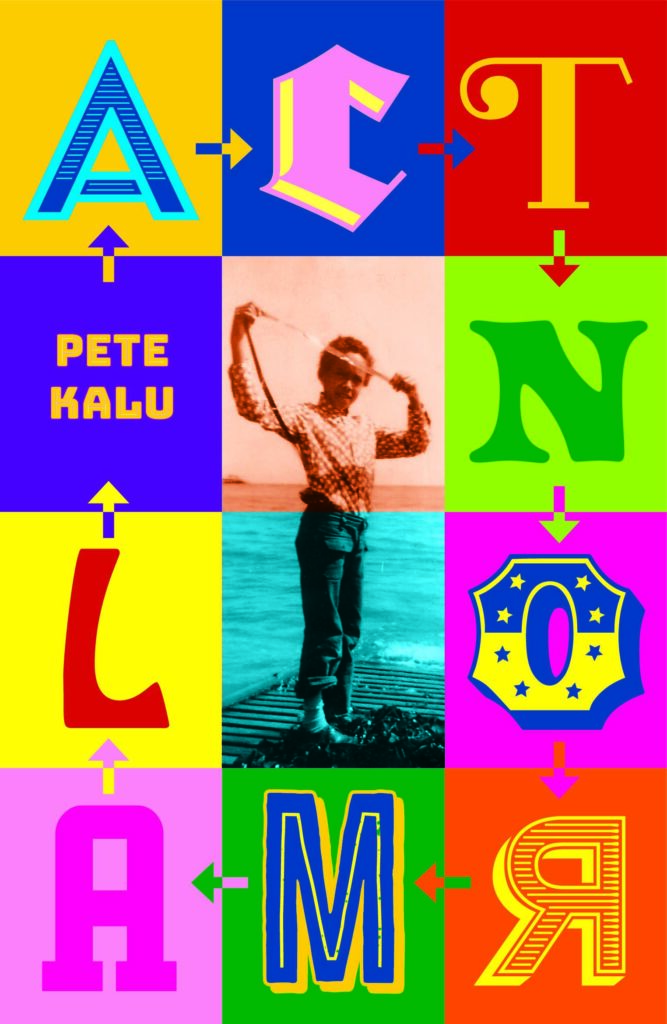

Eileen Pun interviews Pete Kalu about the green shoots of his new book, Act Normal

Eileen: Pete, I applaud the way this book outright talks about how societal norms are absurd at its most innocuous… Or, stifling to a point of exasperation, at its most frustrating, however… what I feel is being exposed in ‘Act Normal’ are conventions that have consequences for a black person that are more sinister than mere absurdity or frustration.

Am I right to read a certain amount of alarm into this work, particularly for black people? In the sense that… does your writing in some way ask us to be vigilant once we come to the realisation that pressures to conform to normality can be detrimental if we comply, but also dangerous if we don’t?

Pete: Thank you for your kind words. Black anger is suppressed. It has to be. If we are to get through life, we have to accommodate discrimination. Take the kidney function scandal ( Racially biased kidney function text exposed ) in which software had an in-built, coded bias against investigating Black people’s kidney issues. Do all those Black people with kidney ailments who were ignored by the doctors because of that biased software now rage? That’s just one example. Rage is exhausting. You burn out. Instead, for the most part, we keep our head down. We joke. We riff. We act normal. If we are artists, we sublimate that rage in works of art, we plant this bitter seed of Absurdity and allow it to grow a tree of strange artistic fruits for the world to sample. The sinister of the past and present is recycled as song.

Eileen: I have my own conclusions about the way in which post-colonial attitudes are responsible for a long-standing alienation and disrespect for nature, I wonder if in your reflections, whether themes about normality and the environment surface, even if indirectly?

Pete: My take on it is that modernity and its rally call of progress was a movement out of the rural into the city. Away from nature and into the built environment. At the same time, Empire and the ‘scramble for Africa’ was articulated as European civilisation upgrading backward, savage societies. This set the framework for the disparagement of the natural environment and of living close to nature and a normalisation of the city as the default mode of existence. We’ve all drunk the Kool-Aid of that one. We all aspire to be city dwellers rather than country folk.

Eileen: Due to my own rural disposition, I have often felt ‘abnormal’… a kind of outlier among ‘country folk’ but at least I can find solace in the non-human world… On the other hand, in cities it doesn’t take much for me to lose my bearings, I was drawn to several entries. ‘Getting your bearings’ the weight of the word-choice is apparent… the passage from Black Boy Pub to Sambo’s Grave and the middle passage. Then the town mission is undermined before it is even started, a taut emotional taunt… It is powerful, can you talk more about what inspired these pieces?

Pete: ‘Getting your bearings’ is a dizzy piece. The movement in the text mimics the dizziness of memory, our ability to get lost and forget what is inconvenient because memory, many neuroscientists argue, serves the present. The British in this present period of time have a postcolonial amnesia for all the invasions they (or is it ‘we’ – why do I now switch to ‘they’?) conducted across the world. When questioned on this, their reflex response is that it was simply a small moment in British history not something to create a song and dance or a work of art about. In essence, hush! Yet the built environment speaks and remembers. I found it both absurd that humans forget Empire stuff even though the signs and labels are chiselled into the road signs, building names and the folklore all around them. This contradiction between the two forces, the wilful blindness and material signs is what provoked me to write ‘Getting your bearings’.

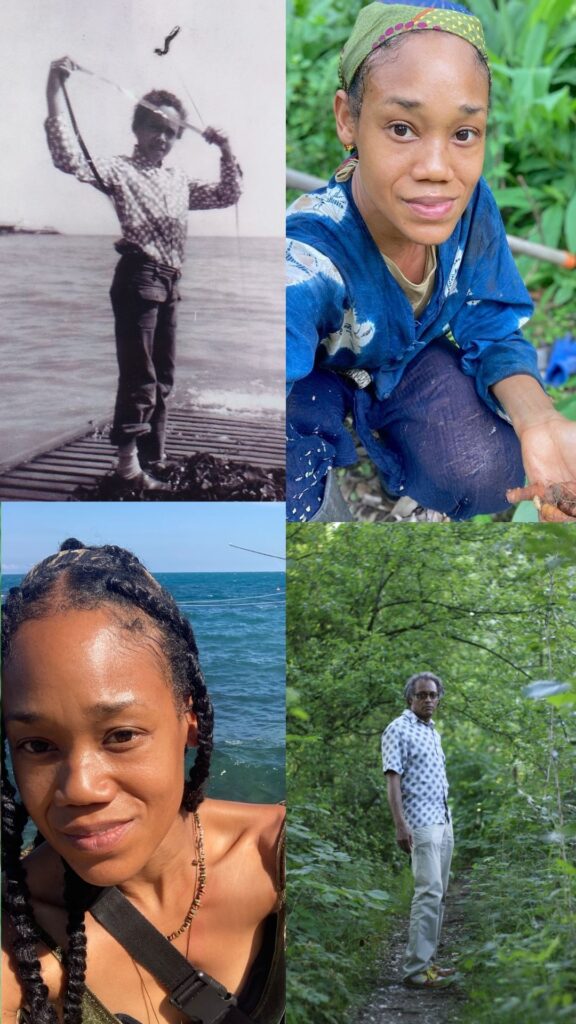

Eileen: On the other had, Getting Lost 1 is confident and relaxed about what might happen unprepared in a forest… there is the thrill of nature, but underlying this is the sanctuary of civilisation. I feel unsettled by this message, even knowing that most people feel exactly like this… The forest is not for living in. What you can share about your experience or the black experience in a rural context… With so much of the black demographic in the UK being urban… I have had conversations with you where rural landscapes are a part of your life experience and have informed your thinking, but to what extent do you feel an urban identity shapes who you feel you must be… how you write, or write about?

Pete: Yes, the ‘Getting Lost 1’ passage surrenders to the trope of countryside as a site of horror – the version seen in the magnificent Get Out movie, and the equally scary, earlier movie, The Blair Witch Project. I was a keen gardener from the age of seven and my visits to the countryside – on church camps in the hills of Castleton or to Ulverston in Lake District where my adopted grandparents retired to – were always happy occasions. The spark for Getting Lost was driving with my youngest daughter through Derbyshire when she was 15. I got lost. Like, I’d follow a bus thinking it would take me back to the city and it would be going the other way- deeper into the hills! The passage folds all these energies into it. I do think being streetwise and city-savvy is part of the urban black profile, and the piece does align with that. Yet more and more black people getting into the green movement. Sometimes in small ways. Growing flowers on their balconies, taking on allotments, and being more assertive about going on walks in the countryside, however hostile the locals. Through my writing, I’m documenting that.

Eileen: I want to quote: ‘We are not safe from Goldilocks, even in the woods’ as striking to me when I think about the appetite of industry capitalism as it relates to slavery, deforestation, bound somehow to her ‘sugary locks’… What made you choose the format of the fairytale? When did you realise that Goldilocks was detestable, as a child? As an adult?

Pete: I loved the Goldilocks story as a child. I wanted to be her, eat off all those bowls of porridge! It was only as an adult that I started to have misgivings, wondering at the story’s origins. I dreamt the story. The link with the Maroons, the equation of the bears with escaped, formerly enslaved Africans, flipping Goldilocks from cute to evil, the forest under attack, all these things occurred in the dream. I just wrote the dream down.

Eileen: As you can guess, as much as your book touches on so many topics, what I found missing is any reference or anecdote to martial arts and Kungfu (gongfu) which, if you can recall, all those years ago when I lived and studied in Manchester was a point of mutual interest between us! Although I wouldn’t go so far as to say that there is a strong connection between black culture and Chinese Kungfu, however, in the 70’s and 80’s when Bruce Lee was a popular icon, there seemed to be a degree of identification of from people of colour about a charismatic, non-white hero that made an impression on black men. As a black man growing up at that time, and that you took martial arts training seriously for a spell in your life… is that a fair statement? Why do you think this topic hadn’t made the cut for this memoir?

Pete: Those were good times back then as fired up, martial arts fanatics! I was loathe to include Gongfu practitioners in Act Normal, despite having the stories, because if they come after you, you’re in serious trouble! More seriously, I don’t think I have fully processed some spells in my life, and so I’ve not yet tried writing them. Your prompting of me does make me think, maybe I could write five martial arts shorts that hang together like the broken mirrors at the end of Bruce Lee’s Enter The Dragon movie! It’s true that we black kids back then were fascinated with Bruce Lee. Not just for the expression of power and his underdog ability to sock it to the powerful white man (usually the karate champion, Chuck Norris in the films). Bruce Lee and his movies were also symbolic of and a temporary antidote for all our struggles with racism at the time. He was our own Superman. We sublimated all our anger and rage by getting into Kung fu. Black kids were leaping off bus shelters, flinging high kicks up in playing fields and gyms across the country at that time. Bruce Lee’s philosophy was appealing too to young black minds. He was a rebel. He broke convention. ‘Be like water’ – flow, be flexible, be vital, be indestructible this way. He created that tombstone quote that said: ‘In memory of a once fluid man, crammed and distorted by the classical mess.’ That quote was powerful too. Reject tradition. Question convention. Think for yourself. Investigate. ‘The classical mess’ can be read as the usual suspect – white supremacy. Bruce Lee was so cool. He could dance too. He was a cha-cha champion before he got into kung fu. How cool is that?

Eileen: Before we close… I absolutely love the tragi-comic sentiment of Radishes… as a grower and poet myself there comes those moments when the things we cultivate and find so important is just a novelty wearing thin for everyone else! Can you expound on this idea that ‘people didn’t appreciate a good thing’? Why are homegrown radishes and writing good? What do you think that lack of appreciation says about normality?

Pete: Sadly for young me, radishes are something most people will have an upper limit on, consumption wise. Yet somewhere, there were people who would have taken my surplus radishes, I just needed to expand the pool of eaters beyond family. You have to find your people. The ones who will love you for what you do, for what you produce. Same thing with writing. Go where you’re appreciated. Somewhere there’s a town that loves radishes as much as you. Somewhere there’s a village that will love your quirky stories.

Eileen: Yes, a little bit hilarious… and also tinged with longing, this quest to find… (you said town), I might say, ‘a village’ of radish lovers. How unrequited our writing endeavours can be, right? This interview has made me laugh and reflect so much, which says so much about the richness of your book. Can memoirs have sequels? Thank you Pete.

Pete: Thanks for this stimulating interview.

Act Normal is available at all book outlets – bookshop.com, Amazon, Waterstones etc. You can find out more and order a copy of Act Normal directly from the publisher here:

https://www.hoperoadpublishing.com/books/act-normal-joy-and-despair-postcolonial-britain: Dreaming in Black and Green