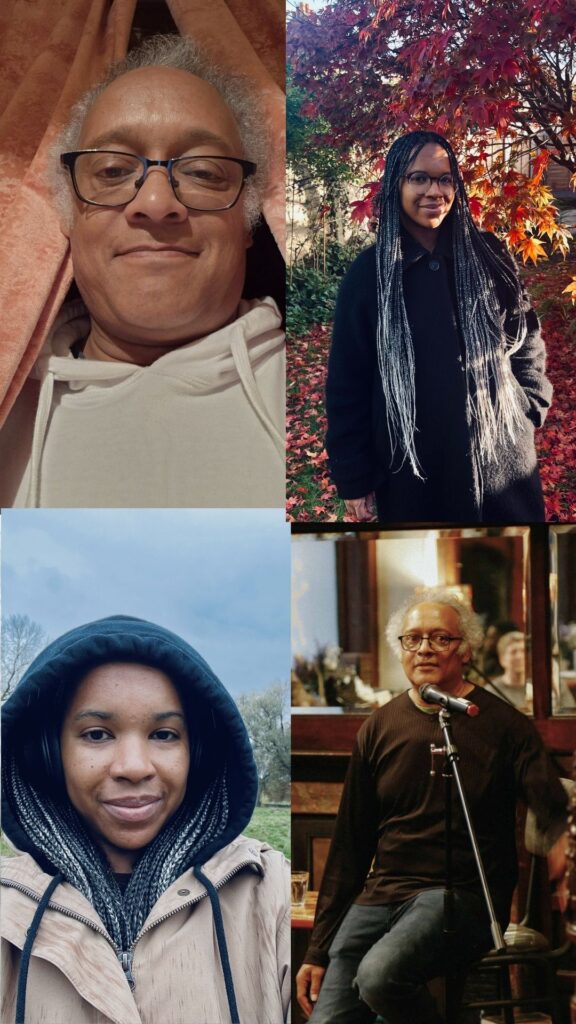

Interview by Amna Bagadi

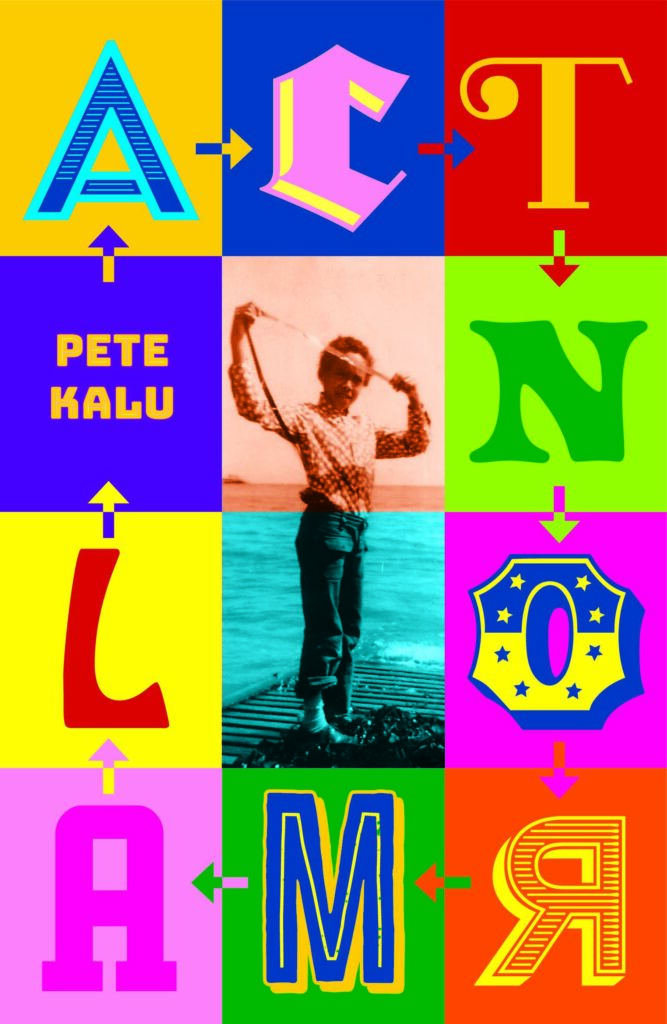

Pete Kalu, a short story writer, novelist, fellow of the Royal Society of Literature, my former boss and agitator, a mentor to many, community activist, former stilt walker, has written and published an incredible new memoir called Act Normal. It talks unflinchingly about the Black British experience, particularly in the North West of England. I spoke to him about how the book came about, what he means by Act Normal, and what he hopes readers and writers alike will take away from it.

Amna Bagadi: The overwhelming feeling I got when I started reading the book was like a rush or a release, a bough breaking. The quiet part finally being said out loud – which was deeply enjoyable to read! So I’m curious, what was the catalyst for the book?

Pete Kalu: Thanks, I’m glad you enjoyed it. I was in an iconoclastic mood. I wanted to drive a horse and carriage though the model of the conventional memoir – I’d read about thirty of them one after the other because I was judging a competition – and I got bored with the formula. So the project became to wreck that, then rebuild the form using ideas from other sources – eg. from neuroscience’s often counter-intuitive understanding of memory, from French examples of biography-essay mergers and from English movements in the popular essay. The essay is going through so much change at the moment as a form. Parallel with all that, I’m a big fan of Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy, Ignatius Sancho’s Letters and Jonathan Swift’s Tales of a Tub. So, it became a mash-up of all those things.

AB: You mentioned that you were inspired by Britain’s first Black diarist, Ignatius Sancho. How did Sancho’s work influence your approach to writing Act Normal, and in what ways is your memoir a tribute to his writing?

PK: Reading Sancho’s Letters, it struck me as the earliest example of the day-to-day consciousness of a Black person in Britain. The musings of an ordinary black bloke. The writings of Equiano and the stories of Henry Box Brown are very much penned for a public audience. Whereas Sancho was close to being a diarist, just jotting his thoughts down on the day’s minor incidents – did it rain, am I broke this week, is cabbage in season? That is what I loved about it. I specifically echo some of his jottings. Like the bits about standing in a queue wanting to buy a lottery ticket and wondering how to get lucky, about giving advice to a young person only for it to be completely ignored. And wondering if there is enough cash flow to see me through the week. I’m such a fan. I have a whole sheaf of Sancho-like writings. I only included a few in Act Normal.

AB: What does the title Act Normal mean to you?

PK: It came from the language of the 70’s TV bank robbery – where the robber would pass a note to the terrified teller saying ‘Act Normal!’ More widely, I love the indeterminacy of the phrase – it begs the question, what is normal? It’s curious, and allows each reader to fill the gap in their own way.

AB: I really enjoyed the format, punchy, a bit trippy and hallucinogenic sometimes, almost algorithmic in length. A great way to tackle memory in fits and bursts. You describe Act Normal as “part memoir, part auto-fiction, part diary,” with the narrative presented in 250 mini-essays and vignettes. Can you talk about the structure and form?

PK: I had one large question in mind: can a memoir mirror consciousness? Can it show all the thoughts, feelings, ideas, patterns, leaps, hallucinations, imaginings, fears, ecstasies that make up (at least my) consciousness? I wanted a form that might allow that and would allow tone shifts and style shits to reflect how I felt my own thinking and feelings changed across a day. Then somehow, I had to make it cohere as a work of literature which, by definition, demands pattern. Those two forces – mirroring yet patterning determined the structure.

AB: The voice and perspective also jumps around, why did you choose to do that?

PK: I was interested by an Italian philosopher, Adriana Cavarrero’s suggestion in her book ‘Relating Narratives’ that the sense of ‘who we are’ (as opposed to ‘what we are’) comes from the stories told about us by other people. She invokes Romeo & Juliet and Ulysees to ask, what would it be like to arrive incognito at the telling of your own story? I try to enact that idea thorough shifts of perspectives and voice I’m not saying I understood fully all Cavarero’s ideas, but she was a jumping-off point.

AB: It’s a proud Mancunian book as well. In the book you say Black Britishness should be tied to a Mancunian identity, instead of being confined to a London one. Talk about this, this assertion of a British north west identity is a strong theme running through the book.

PK: The Black voice in Britain has too often been reduced to the noises coming out of London. For a while, I went along. I set one of my novels in London and it did very well, I even ended up writing a column for a local London newspaper on daily London life – when I was living in Manchester! But, after a while, I decided to resist the pull of the ‘Black British = London’ stereotype. I have a piece in Act Normal saying “the Black North needs an army.” I was interviewed about it once by the Guardian I think, and in the act of being interviewed, I found myself getting more and more annoyed at how ‘London, London, London’ everything was when it came to official Black culture – it got me fired up!

AB: The book also feels very timely, particularly in light of the riots last year in the summer and this year’s “far right” (fascist) marches. It was interesting to read your experiences with racism, particularly as a child and teenager. When you reflect on it, what are your thoughts about where things stand now, compared to how they were before?

PK: As a system of oppression racism moves with the times. P**i and n****r were the words in my time, even as recently as 30 years ago, P**i was the choice of insult to brown-skinned people. Now, with the rise of Islamophobia and all the labels that trail in with that (let’s not use them here) there’s a new language of hate, and new legislation and policies that enact racism. That’s what my essay ‘Theseus and the ship of Racism’ touches upon. At the same time, the world is becoming multi-polar, the European / American hegemony is waning, Black and Brown people will not forever be under the thumb of European and American powers. So these atavistic energies are doomed to fail. Globally, things have improved, and they will keep improving though it is never a straight line, always a back and forth. For example, mixed marriages in the 1970’s were considered distasteful in mainstream culture – an act of miscegenation. Now they are almost normal (there’s that word again!). Take urban geography. Black people can now live without too many eyebrows raised in a lot more places, not just ‘the ghetto’. It’s hard to see when you are in the thick of some contemporary battle, like the current hostile environment policy or a ‘Sink the Boats’ mania. But the jagged curve of progress is rising slowly upwards. I’m an optimist!

AB: What would you like readers (and other writers) to take away from this book?

PK: A sense of liberation – that it’s OK to be different.

AB: If you could speak to your earlier self with everything you know now, what would you tell him?

PK: Buy Bitcoin as soon as it comes out. Joking aside, hang in there. The going will be tough, and sometimes your problems will seem insurmountable, but you have allies, you will have brilliantly supportive people around you who will hold you, be there for you. You will get through this. Pretty much what I wrote in ‘Running the river’.

AB: What was the most surprising thing you discovered about yourself in writing this book?

PK: I was able to let go of everything school and later university had taught me about writing essays. Having been schooled and inculcated in logic, order, the rules of rhetoric and analysis, the correct way to present evidence, marshal facts and build conclusions that win cases and convince, I had to find a different approach, one that was intuitive and trusted all that the old way deliberately walled off as erroneous.

AB: You have a long career as a poet and fiction writer. How was writing this memoir different from your previous work? Was it more challenging to write about your own life?

PK: There’s something about my own life in every book I’ve written. My Young Adult novel, ‘Silent Striker’ went into detail on my experience of deafness, mediated of course by the main protagonist Marcus. I’ve also been writing semi-autobiographical short stories and blog pieces that were getting published in places like Writers Mosaic, and getting a great reception there. That emboldened me. Coming back to your Manchester question, it’s been good, writing firmly from the position of Manchester as well. London and Leeds are well served – they get good profile for Black writing in those places. I wanted to get Manchester bigger on that map too. So there is a rep element to it – I’m repping Manchester!

AB: How does it feel to have a memoir out there?

PK: Scary. I imagine two angry groups of people. The first group angry because they are in the book (or imagine themselves to be). The second group angry because they are not in the book! It’s been fine though. I’m still alive.

AB: I’m not in it, but I’ve gotten over it! Thanks for speaking with me Pete! And thank you for this wonderful book and enjoy it taking on its own life as it goes out into the world.

Act Normal is available in all good bookshops now – two bookshop links and a link to a sample from the book below…

https://www.hoperoadpublishing.com/books/act-normal-joy-and-despair-postcolonial-britain

https://www.amazon.co.uk/Act-Normal-despair-Postcolonial-Britain/dp/1913109445

http://creativewritingatleicester.blogspot.com/2025/11/peter-kalu-act-normal.html?m=1: Act Normal – Amna Bagadi interviews author Pete Kalu about his new book.