When 15-year-old Nathan’s older brother Al (17), kills himself, Nathan is distraught. There appears to be no rhyme or reason to his brother’s act. And The Stars Were Burning Brightly follows Nathan as he navigates his grief and tries to uncover what pushed his brother over the edge. Framed this way, And The Stars follows the classic ‘victim-of-crime’ crime novel genre dynamic as expounded by two masters of the genre Boileau and Narcejac (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boileau-Narcejac for more on them). As they put it: ‘One becomes a victim as soon as one is present at events whose definitive meaning one is unable to decipher … The crime story, instead of signalling the triumph of logic, has then to consecrate the failure of rational thought: it is precisely for this reason that its hero is a victim’. The victim-of-crime novel is a study in the anguish of the loved ones who survive the victim’s death. And the survivors’ attempts to find a reason why is of course doomed to be unsatisfying since, on an existential plane, nothing discovered can ever bring the victim back.

Specifically, Nathan’s quest is a means for him to wrestle with his sense of culpability: he had not noticed trouble brewing in his brother’s life. What part did I play in his death? Nathan asks himself: could I have done anything differently and prevented it?

The tale is told in the first person through three viewpoints: that of Nathan, of Al’s close friend, Megan, and, using phone messages and other epistolary devices, that of Al himself. It is a victim novel, but there is also a very sweet love story swirling around the fraught issue of Al’s suicide, a love story delicately stitched and sensitively developed.

As the plot thickens, some topical Young Adult themes come to the fore. On of those is the nature of identity, particularly, the strange way in which one person can know and yet completely not-know another person. In the eyes of Nathan, Al was perfect. Yet, in the eyes of his school peer group, Nathan learns, Al was a geek: too brainy, too remote, uncool. The reader discovers that Al was a talented painter and had a wide-ranging curiosity for subjects as diverse as Astronomy, Biology, Botany and Maths. Al was ostracised by the working-class youth culture he lived within. Are working-class communities (or, perhaps, on a different analysis, all youth cultures) inherently hostile to gifted yet introverted young people? If so, how do young dreamers and thinkers navigate that? Other themes developed in the novel include how social media can make bullying more intense and inescapable; and the dangers of online identity deceptions such as catfishing.

The novel is set in Wythenshawe, Manchester, and the characters speak at times using Wythenshawe-inflected language patterns and phrases (such as using ‘proper’ as an intensifier as in: ‘that’s proper good’). Nathan, the main protagonist, is of mixed heritage, his absent father black, his mother white. The conjunction of blackness and Wythenshawe speech may be a departure of sorts in that I cannot recall that any writer before has given voice to such a character. Across town (ie Manchester), the crime writer, Karline Smith has delivered a series of novels and stories in the voice of inner city South Central Manchester where West Indian Englishes still infuse third generation black language codes. Jawando is doing something different. I recognised the Wythenshawe speech (I went to school in Wythenshawe). It quickly becomes normal within the novel, and so invisible after the first few chapters, and it is a deep pleasure, a small but important act of assertion, to see this set down in a book.

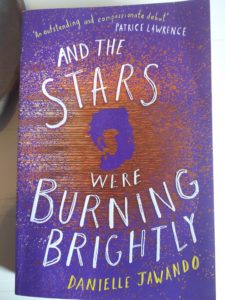

One of the bravest and most difficult things a writer can do is take their own trauma and explore it through art. Sometimes, by doing so, the artist tames the trauma. I say, sometimes because it is not always possible, the process can kill you (see arguably, the life story of Van Gogh, an artist whose life and its relationship with his art is featured significantly in And The Stars). But go into that trauma, an artist sometimes must. It was a risk that, for Jawando, proved very much worth taking. And The Stars Were Burning Brightly is a compelling read, dealing with difficult subjects deftly and compassionately, and wholly without any sense of mawkishness.