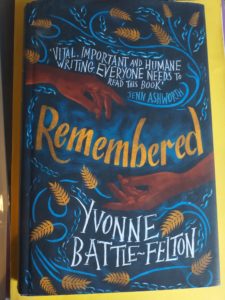

On February 20, 1910 in Philadelphia, a black man (Edward), drove a railroad trolley into a department store, killing a number of people, injuring others. Why did he do it? This is the plot premise of Remembered, a superbly evocative and moving novel by Yvonne Battle-Felton. The novel looks at America during the time of plantation slavery and at sixty years of slavery’s long-tailed aftermath there. Remembered is written primarily in the voice of Edward’s mother, Spring, and oscillates between events in 1910 and the formative years of Spring’s life, including Spring’s enslavement, her life as an enslaved person and after emancipation in the early 1860’s. The narrative stitches the connections between these different times to deliver a haunting tapestry of the horror, jangle and stink of the era.

Narrator, Spring is shadowed by her dead sister, Tempe. Early in the novel, Edward is lying in a coma on his hospital death-bed. Spring and the ghostly Tempe argue over what happens next. If Edward dies, they agree, he needs to die right: to come to the afterlife with full knowledge. Tempe points out he does not know the full story of his mother. Spring says she will tell him, but ‘Either I’ll tell it my way or it won’t get told.’ Spring proceeds to do just that.

We learn the story of Spring’s origins and wider family. The telling is Spring’s, and of Spring’s family, but the novel also opens out as an act of remembrance for all those individuals who endured through slavery. Their stories are not captured in official documents. White writers and administrators did not see fit to record their lives. Pen and paper stories were not written down by enslaved Africans for obvious reasons. Addressing this historical erasure and recovering the stories of people like Spring is a path embarked upon most determinedly by Toni Morrison (eg. Beloved). Of course, there is much unearthed by these stories that white society might – then and now – want to look away from. The cruelty that the Philadelphian Walker plantation Patriarch meted out in Remembered parallels the degradation forced upon enslaved Africans working on Jamaican plantations such as those of James Robert Wedderburn ( https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/person/view/2146643591) and the notorious Thomas Thistlewood (https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/person/view/2146651067). In venturing into these waters, Battle-Felton joins Morrison in a commitment to ‘speak the unspeakable’, to borrow a Morrison phrase.

As a writer, I was interested in some philosophical questions that Remembered had to work through. What was it like in those times – not on the poetic or epic scale – but on the level of the day-to-day, the level at which the novel as a form excels? Can these horrors be described and at the same time juxtaposed and made to seem an organic part of the wider world of that time? How do you balance horror and the everyday? Who were we then, as human beings? How did we see the world? The writer, Henry James, in a letter, wrote that the task of recreating the consciousness of those who lived in long-ago times was ‘almost impossible’. Is it? The other large question I was interested in concerns how the novel as a form is employed by black writers. A novel establishes a world and in doing so constitutes a world view. Is that world view necessarily Western? Remembered sits in conversation with Beloved by Toni Morrison, The Famished Road by Ben Okri and Their Eyes Were watching God by Zora Neale Hurston. In all three there is a sense of Africanist cosmology running through, signalled most strongly in Remembered by the ease with which the dead sister, Tempe arrives in scenes where her sister, Spring is present.

Moving to a radical black arts type critique, another question raised by such novels, though much less spoken about, is the Malcolm X-esque question: how did white people manage to do this to us? Were we complicit? Weak? Fools? In that mode, Remembered stirs, within a black reader at least, an incandescent rage, and for moments, as the degradation, rape, humiliation is described, there is a reader-character unity with the black characters in Remembered as explanations are bewilderingly advanced, including, in a moment of splitting, the idea advanced by the patriarch slave master Walker himself, that white people got ‘nothing but the devil’ in them.

There are harrowing scenes in Remembered. But also moments of sublime transcendence. One of the most delightful is Battle-Felton’s answer to the question, what was that moment of freedom like for enslaved Africans in Philadelphia when slavery was finally abolished? Of course, the news of abolition does not filter to everyone all at once, but in bits and pieces. And there features in Remembered an almost dazed phase of drifting and wandering of the newly free, an assuming of new names, a beginning of new directions. Battle-Felton renders this numinously and imaginatively: I’ve not encountered in literature this moment expressed so evocatively before.

I’m always interested in a novel’s stylistics: the particular technical choices made by the author to bring a story to life. Here are some tentative notes on Battle-Felton’s choices for Remembered:

It is written partly in the first person ‘I’. This sets some limits on prose style with these sections (for more on this, see, for example the first five short sections of James’ Wood’s How Novels Work on ‘free indirect speech’) so the poetry here is mostly in the speech patterns and inner vision of the characters. Battle-Felton works this stylistic vein excellently: I found myself reading certain lines again and again, trying to figure out, just how did she make that line sing so well? Here are a few, all taken from page 11:

Snatches of conversation slap me in the face, sting my cheeks.

Children clamor noisly down 20th Street. On 21st, horns honk, heel click, people yell.

Suddenly, everybody know my boy. People ain’t said hardly two words to him acting like they know what goes on in his head.

Returning a little to a previous focus, the pain of what happened to enslaved Africans during slavery times may well be close to unspeakable. How does a writer find a narrative position from which to describe that pain, a position that it is neither under-distanced (rant) or over-distanced (fact-laden, documentary). The section on commentary in Wayne C Booth’s The Rhetoric of Fiction explores this dilemma well. Some of the literary devices used by Battle-Felton are: switching between first person and third person, section length, the merging of different time signatures, the movement between present tense and past, alienation techniques, use of the passive voice, contrast, rhythm, and musicality or patterning in the dialogue and descriptions. These techniques, among others, remove the raw pain of deeds described for instance in Chapter 6 of Remembered, or, at least, mitigate that pain.

A sociologist once said to me that the novel is a bourgeois art form due to its focus on the individual, both in terms of characters and the act of reading – which is a solitary activity; contrast this, they argued, with, say, music which generally requires collaboration between musical instruments to come alive and works best with an audience of more than one to generate its aesthetics: the novel’s entire inclination is towards heroic individualism! Taking their argument as valid for now, and assuming an ambition to paint a picture of collective action within the novel, how has Battle-Felton worked around this weakness of artform? Firstly, Remembered is not a tale of individual leaders or heroes. Spring, Tempe and Edward are representative of ordinary people who, if it were not for the novel, would be forgotten since, as a character states bluntly toward the end of the novel, ‘Average men are forgotten. Heroes aren’t.’ A second mitigation is the use of gatherings as part of the action of the novel: people come together to express solidarity, to uplift and revive – in kitchens, in clearings, by rivers, in basements, at church. By these rhetorical means, Remembered signals the strengths of community, and the support a community lends to the individual. It is not the standard Western novel story arc featuring the heroic singular journey of one individual or any one family. The novel subtly suggests survivability is a matter of solidarity in the face of power, and a matter of the strength that comes in part from an understanding of others’ suffering and its effect on the human mind as much as the body. The remembering work of the novel is a counterpoint to historical erasure around slavery, and to the cold, extant records kept by slave owners; it is in the fictional mode of familial, lineal remembering, but also, multiplied exponentially, fictive family by family, book by book, a community knowledge: the things we must not forget, for the novelist has picked up the baton passed to the next generation by Morrison: remember these folks, Morrison urged us through her own works, and how they came through their times. Yvonne Battle-Felton has written a moving, memorable, finely-crafted novel.