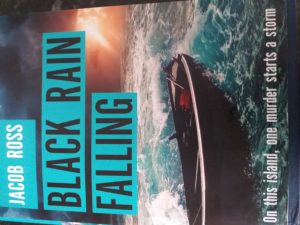

Black Rain Falling is a cracking crime novel by Jacob Ross, the second in his ‘Digger’ Digson series, set in the fictional Caribbean island of Camaho. Crime writers occupying the highest plinths of the crime fiction pantheon – Mosley, Neely, Hammett, Highsmith and Chandler – might give Ross a nod for his achievement: he has a consummate talent for balancing the various energies needed for a contemporary crime story – action, suspense, sustained multi-faceted evolution of major characters – all the while weaving a yarn that engrosses. It helps that Ross has an indecent raft of sheer writing verve. This writerly review looks at some elements of what Ross does.

Setting, Modernity, the crime novel and Black Rain Falling

The term modernity was coined by Baudelaire in his essay, The Painter of Modern Life. He saw it as inextricably bound up with the city and the shock of the new: ‘the fleeting, ephemeral experience of life in an urban metropolis’. One of crime fiction’s earliest pioneers was Edgar Allen Poe. Poe’s short story Murder at the Rue Morgue is often advanced as the very first detective story, and is set in the city. Conan Doyle and his Sherlock Holmes stories lifted many ideas intrinsic to our understanding of ‘the city’ from Poe and from the French pioneer, Gaboriau. So it came to be that detective fiction and the city became linked in the popular imagination. When this genre history is hooked to black presence, which in the UK and in USA has often been clustered around cities, then it is no surprise that the major black practitioners of crime fiction – Barbara Neely, Walter Mosley, Attica Locke in the USA; in the UK, Dreda Say Mitchell, Courttia Newland and Mike Phillips, among others, have invariably set their novels in a fictitious or actual city. Ross’s ‘Digger’ series is different. The action takes place on the fictitious Caribbean island of Camaho (pop. 100,000). Ross himself was born in Grenada, and his love of the Caribbean permeates Black Rain Falling. His Camaho world is a particularly Caribbean mix of the urban town/city, and the village. Ross’s other works (particularly his novel Pynter Bender, but also many of his short stories), evidence a keen poetic sensibility and, in venturing into crime fiction, Ross has not abandoned this gift: a sense of poetry infuses his crime novels. Nowhere does Ross’s lyricism ride higher than when he describes the Camaho natural environment. There are sentences other writers would die for in the descriptions. Here are a few examples:

‘All month it had been like this: dry, dusting, sapping; the air filled with the lament of suffering livestock that were hugging the shadows of he forest receding all the way to the hilltops. With all that dryness a pusson felt afraid to strike a match.’

‘The slope of a hill, the type and thickness of the vegetation made a sound when the wind ran over it, that a pusson heard nowhere else in the world. Up here, among the ferns and bamboo and ancient thick-headed trees, the Belvedere mountains sobbed and mourned.’ (Shades of Miss Smilla’s Feeling For Snow)

‘Old Hope village spread out across the hillside on which we lived. Directly ahead were the foothills, pulling my gaze all the way up to the Mardi Gras mountains – purple-dark in the early light.’

Western rationality, African Cosmology and Black Rain Falling

Western rationalism has often been the go-to default for crime fiction, indeed there are aspects of the crime genre, especially its centring of science, rationality and logic, that make crime fiction in many of its iterations a paean to Western Progress and rationalism. However, there are other cosmologies in existence, and black writers have often explored the literary potential of giving the narrative breath of life to non-Western ways of seeing the world (egs: Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart, Helen Oyeyemi’s Mr Fox, Ben Okri’s The Famished Road, Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God, Toni Morrison’s Beloved, Nii Ayikwei Parkes’ Tail of the Bluebird; many of the short stories of Leone Ross and Ironesen Okojie). Black crime writers do this while still maintaining some of the genre’s standard detective tropes of logic and rationalism. Where is Black Rain Falling positioned in this Western materialism – Africanist cosmology dialectic? Early on in the novel, a glimmer of non-Western cosmology is given. Digson tells of how his grandmother, who raised him, described the world to him:

‘Olokun is the god-woman of the Dark waters. She rule the bottom of the ocean, yunno. The only one who know what happen to all them African who never reach this side of the Atlantic.’

As with Digson’s grandmother, the Camaho rural women are the major repositories of knowledge based on an alternative cosmology. They carry a spiritual connection with the land and the history of the people within their customs, manners and oral stories. When Digson sees a group of women gathering urgently:

‘They brought to mind my grandmother, who had mothered me, muttering in a closed room with other women that she’d gathered around her. I remembered the secrecy of their ritual cleansing – women, preparing one of their own for the trouble to come.’

‘These elders would be carrying in their heads the family tree of every person on Kara Island and their connections to each other. They still named their children in the language their people brought with them across the Atlantic a few centuries ago.’

‘They still held on to fragments of their old languages, cherished their bloodlines, built tombstones for ancestors that were more expensive than the homes they lived in.’

By way of contrast, Digson we are told, trained in Forensics in England; the novel has a drip-feed of forensic insights showing how dead bodies provide information to a forensic scientist. Yet Digson’s power to solve a case relies as much on his guidance by the village women regarding the islands’ emotional and spiritual pathways. For instance, as part of his murder investigation, Digger is trying to locate the hidden, dead body of an old man, Koku. Digger simply cannot find the body, and neither, for two years, has anybody else. The need becomes urgent. Leave it with us, say the village women, we will work it out. And they do, their tools for discovery being emotional geography and affective cartography. The novel is tellingly silent on the specifics of their detective skills. The price Digson has to pay for their assistance is that he has to leave the body where it is, undisturbed because, as their formidable leader Benna tells him, ‘Koku not crossing no long-water no more. He already where he s’pose to be.’

The (Smith &) Western influence

The influence of the American Western genre glints now and again in Black Rain Falling. Two touches I enjoyed: Digger’s partner Miss Stanislaus twice does a pistol spin worthy of a Louis L’Amour riff. And Digger himself employs a quirkily unique weapon, a whip-like old leather belt which wakes a faint memory in me of the Western heroes’ rawhide whips. This Wild Western connection is not casual from a genre point of view. Leading USA crime writer Elmore Leonard began his writing career writing Westerns. He and others have noted the two genres’ points of similarity, prominent among the similarities being the lone outsider hero and the hostile environment in which that individual operates. Cormac McCarthy’s The Road exemplifies the ultra-modern New-Western text, McCarthy’s novels arc-ing into the epic by their symbolic excavation of a post-apocalyptic wilderness and dissection of the nature of ‘aloneness’. Ross departs significantly and importantly from the Western-crime fiction Outsider template in several major ways. His protagonist Digger is for sure a maverick. But he is no exiled outsider, rather born and raised in the area in which he operates. Although Digger possesses fine detective skills, to reprise some thoughts from the section above, one of the novel elements of Black Rain Falling is Ross’s counterpointing of individual heroism with a community knowledge without which Digger would never succeed. Time and again in Black Rain Falling, Digger’s respectful rapport with villagers, particularly the older women, allows him to unravel some knotty part of the crime mystery he is faced with.

Choice of main protagonist

The crime novel allows many different types of protagonist. They can be the perpetrator (eg. Patricia Highsmith’s Mr Ripley series); victim (see the Boileau-Narcejac victim novels); or Investigator (see Chandler, Hammett, etc). The Noir variant of the crime novel sees a Modernist oscillation across these roles (in line with Modernism’s concern with flux, anxiety instability, dishonesty, the impossibility of certainty). Black Rain Falling has, in ‘Digger’ Digson a classical (as opposed to Modernist), stable narrator. We ride along with his actions never once considering he is anything other than fundamentally a good guy, and with an implicit understanding that he will overcome the short-term challenges of solving the case. There is a (plot-wise) minor element of victim to Digson’s profile in that his mother was killed by the Camaho police force and her killing covered up. Digson is playing a long game – seeking to bring his mother’s killers to justice but so far (ie. across the two novels – the award-winning Bone Readers and Black Rain Falling), with little success.

Gender

The hard-boiled sub-genre of crime fiction veered away from the Holmes-ian cerebral game and introduced a Masculinist turn. In this sub-genre, protagonists are placed in physical danger and use physical violence as much as cerebral acuity to pull themselves out of that danger. A hard-boiled, Masculinist element is displayed in Black Rain Falling by both female and male Investigators: there are physical fights, with fists, belt-whips and guns. That said, the main character Digger has a feminist worldview and a deeply caring, compassionate side. These are not decorative add-ons to the novel. They form a core part of Digson’s psyche and are part and parcel of his investigatory strength. On so many occasions within the novel, minor characters yield information only by dint of Digson’s astute and empathetic questioning; he is able to engage everyone – from the scatter-prone village children, to the see-everything, say-nothing village elders, from the curmudgeonly fishing tackle shop proprietor to the sophisticated Camaho socialites; they all possess information the access to which rests on Digson’s skills of empathy and emotional intelligence. Furthermore, Digson is able to recognise the limitations he has as a man, and the better placed ability of his assistant Miss Stanislaus to read some social situations and people; Digson often defers to her judgement. On several occasions, when Digson’s investigation is thwarted and his life in peril, it is Miss Stanislaus who provides a powerful intervention, her acts and insight being central to Digson’s ability to survive, and to solve the case. Miss Stanislaus’s place in the novel is worthy of some further observation.

Kathleen Stanislaus is Digger’s side-kick (she would so object to that term!) in the Camaho CID Department, and the relationship between the two is fascinating. There are undercurrents of sexual attraction between the pair, but this never turns sexual. By this decision and others, the character Digger is constructed in such a way to avoid the sexual stereotype of the hyper-sexual black male, and to foreground the equal and unique skills a woman can bring to the detecting job. Theirs is a partnership of equals. Digson’s romantic relationship is with Dessie Manille, a woman of an altogether different make-up to Miss Stanislaus. In a key scene, Dessie challenges the close bond Digson has with his work partner, Miss Stanislaus. Digson explains it thus:

Dessie sniffed and covered her face with her hands. Then she rose to her feet. ‘So, y’all have a relationship?’

‘You my woman, Dessie. She’s not.’

‘I would’ve preferred you didn’t tell me.’

‘I would’ve preferred you didn’t ask me. Is like you pushing me to choose between air and water.’

‘Which of us is air, Digger? And which is water?’

‘No choice, Dessie. They both important.’

Stylistics

Flaubert’s advice to Maupassant (at the point where Maupassant was moving at the time from being a poet to being a short story writer) was to seek the undiscovered aspect of ordinary things, as a means to get a fresh take, find the exact verb, the exact noun, the exact modifying adjective, not to settle for something close but not quite. This is where the poet in Ross excels. The exact rightness of his description, including his brilliance with what language theorists and philosophers call qualia (for qualia discussion see eg. Thomas Nagel ‘What is it like to be a bat?’) is a joy. Here are some phrases I loved in Black Rain Falling:

‘I thought of an octopus with its body streamlined for flight.’ Describing a small island’s shape.

‘Garveyhale, the tiny town, looked like a stack of seashells with the ocean chewing at its edges.’

‘I waited until the old Datsun grated to a start, watched it shudder out of the concrete courtyard onto the road, loud enough to wake the parish dead.’

‘Friday. Great columns of cloud were gathering over the eastern hills, dulling the day and releasing the occasional measly scattering of rain that only raised the humidity.’

‘Old Hope village spread out across the hillside on which we lived. Directly ahead were the foothills, pulling my gaze all the way up to the Mardi Gras mountains – purple-dark in the early light.’

His skill is particularly present in the short, pithy descriptions of characters that the crime genre exalts:

‘My grandmother – a thin-boned, cinnamon-eyed Afro-Indian, fierce like a hive of hornets when she got stirred up. I’d seen her stand up to men ten times her size with nothing but a rusty machete in one hand and the heavy leather belt she’d taught me to use as a weapon in the other’

‘Charred old men, in their half-drunk stupor, would stare at this bottle-smooth, fine-boned creature as if she were an apparition’ (Miss S)

‘Caran’s lieutenant was a taut young woman – dark-eyed and unsmiling, with a Remington Bushmaster SCR slung from her shoulder.’

‘An old man, bone-thin and shirtless, lowered the corn cob he was sucking on and angled his head at the beach.’

Linguistics

According to Saussure, what is written is always a shorthand representation of the world, a set of signs, not a direct transfer or reproduction. Life does not happen in words. Even speech is its own thing, and words only indirectly (if at all) transpose soundscapes. It follows that the dialogue on the page is as much an act of construction as the story itself. Sam Selvon’s Lonely Londoners conforms to this rule. The Lonely Londoners evokes a sense of Caribbean-ness in the characters’ speech, yet, arguably, its dialogue is an invention, Selvon’s hybridisation of all the different Caribbean ways of speaking at that time in London, with the added ingredient of Selvon’s particular inventiveness. Selvon’s linguistic achievement has never been given the credit it deserves. Turning to the language spoken by the characters in the fictional Camaho, the language is a hybridization of different Caribbean speech patterns turned to text/speech. And the linguistic marvel of Black Rain Falling is that we recognise its Caribbean-ness – it rings true – even though we know, as with Camaho the island, it has to be fictitious; and perhaps one reason for this feel of authenticity is that, like languages in actual existence, the Camaho language is sufficiently sophisticated that it contains within itself a number of variants: The village speech. The uptown high society speech. The Stanislaus lisp. Digsn’s more favela way of speaking. Office talk. Bureaucrat speech. All these inflections and variations are readable in the flow of Black Rain Falling dialogue and, to a lesser extent, in the narrative voice. It makes the linguistic turns of Black Rain Falling a joy: not so remote they are hard to decipher, yet replete with the buzz and snap of a vibrant, nation-language. It is a magical achievement, a product of the author, Ross’s deep knowledge of Caribbean nation languages, and of course, his inventiveness! PS. I can trace Trinidad and Jamaican elements. There has to be Grenadian with it too. Someone more knowledgeable than me may be able to trace others.

Villains, Stuart Hall’s Representations theory on stereotypes, and Black Rain Falling

In his text, Representations, Stuart Hall argues that, in a racialised society, the overload of racial signifiers which reduce the humanity of black people and create stereotypes is a phenomenon that has to be navigated by all black artists. As Hall puts it: ‘everyone – the powerful and the powerless- is caught up, though not on equal terms, in power’s circulation. No one – neither its apparent victims nor its agents – can stand wholly outside its field of operation’.

Hall lists three available responses by black artists: (1) reversing the stereotype: ie. embracing the stereotype and supercharging it. Here, Hall cites the Black is Beautiful movement and Blaxploitaton films; I would add in UK, some of the 90’s Xpress pulp fiction crime novels. (2) substituting positive images for negative ones: eschewing the features of the stereotype and attempting instead to create a portrait that is profoundly, positively different to that of the stereotype; and (3) ‘contesting it from within’: subverting the stereotype by using aesthetic techniques particular to each medium to undermine and subvert its reductive purpose. For this third example, Hall cites the film Looking For Langston by Isaac Julien; in British crime fiction literature I would cite Helen Oyeyemi’s Mr Fox. Hall’s list is not exhaustive, and, elsewhere, I have argued that one other response is the counter-narrative, as best exemplified by Courttia Newland’s early crime fiction texts (in this response, the figure put forward as stereotype by the media is taken up and reworked and given interiority and humanity by the black writer).

Black crime fiction must deal head on with racial stereotypes since all crime fiction requires perpetrators – villains – and if those perpetrators are black, they are easily positioned within the stereotypical signifiers that abound in real life already, aligning the antagonist – the trouble-causer – with the prevailing, mainstream reductive, stereotype of black people. What does Ross do? The murderous antagonists in Black Rain Falling are Juba and Shadowman; a third villain is Luther Caine. Here is Juba, described:

‘I was in the presence of something not quite human, a creature from my grandmother’s story-world of fire-rolling demons and blood-guzzling loup garou that she used to frighten me with as a child.’

The ‘not quite human’ is the Othering that heads into stereotype territory. But Ross adds complexity and subtlety by slowly reworking this initial image: Juba turns out to be the cousin of several other islanders; his real name is known to the older women of the island and details such as his basic and so-human fear of water and incompetence as a sailor, told to Digson, tellingly, by one of the older women, Benna: ‘Juba was a sailorman, she said, but everybody knew he hated water touching him. She wrinkled her nose. S’matter ov fact, he couldn’t steer a boat to save his life.’ His power (and the Big Buck stereotype) is further diminished in the womens’ revelation that they had only held off dealing with Juba because they knew it was only right and proper that he was dealt with by the woman he had raped when she was a schoolgirl, so she could have her closure/revenge: ‘We could’ve put away Juba long time ago. Ain no pusson here who din know Kathleen comin back for him.’ Ultimately, Juba cannot be Othered because on such a small island, he is a part of the community: ‘Like you know, on Camaho, everybody is family.’

The equation of: blackness = evil is further undermined by what I would call the chromatics of the antagonists. The prime mover of all the evil, is not the darkest-skinned man but instead, Luther Caine, a man described as: ‘Fair-skinned, grey-green eyes, all teeth – a Caucasoid Negro. Light-blue linen jacket. Matching raw silk trousers…’ The description picks up political resonance because of the earlier sketch of the island’s history and politics by reference to the portraits hanging in the Camaho Police Commissioner’s office: ‘[A] long row of portraits of white stiff-backed colonials; after them a couple of light-skinned Barbadian mulattoes, after them the ‘brownings’; and now the milked cocoa of my father. Another coupla decades or so, they’d probably be obsidian.’

There are plenty of other aspects to Black Rain Falling I could draw attention to. But, at 3000+ words, this review seems to be attempting to become a novel itself. I may add a few more thoughts later, but, rather than revisiting and ploughing through any more of my lifeless prose, I recommend you go buy and read Black Rain Falling. It’s an absorbing novel, and it may change how you see yourself, and the world.