Ankeli’s paintings vary in size from A4 landscapes to metre x metre plus squares. They are predominantly acrylic on canvas, often incorporating lightweight ‘found objects’. The prices range from 150 pounds to just under two thousand pounds. The exhibition runs till 2 Dec 2018.

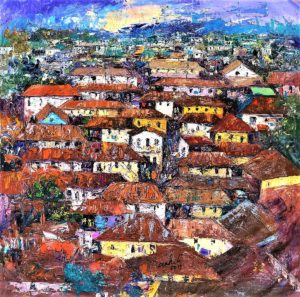

Townships and streetscapes have become a standard of the African painting market. Where are Ankeli’s located? Architectural and street life tropes in his works suggest the setting is more likely Lagos than the north Nigeria of Ankeli’s birthplace. I have a variation on the street life painting view – a narrow painting of yellow buses in traffic, by the artist, Sokanu, on my wall. They are popular subjects. What appeals in them? I visited the district of Mushin in Lagos years ago. The roadside there is full of noise from a thousand sources, the air blows up with scents and smoke, there is a chaos of movement especially in rush hours. Painting mutes all audio and movement and allows the mind to home in and contemplate the visual. In Ankeli’s paintings, the housing assumes a more symmetrical aspect, boosting both the geometric patterns and the colour harmonies that you miss when in the thick of the scene. Ankeli’s ‘scapes have vibrancy and an upbeat symmetry. The colours: brightly lit old blue, strong orange, deep rust and traffic light yellow, all work in harmony; ultimately the painting feels like a panoramic vista that someone nostalgic for urban Nigeria might want to acquire.

Another painting in the exhibition – and there are variations of this type on display – is the Couple painting. It is clearly mixed media: gauzes, ribbons, rope or string, tubing, threads, other small found materials applied to enhance, compliment or integrate with the basic acrylic paint marks.

Found objects have a sympathy for lost people, the poor and downtrodden. Ankeli’s paintings of this type are not anarchic or full of revolutionary zeal – he does not depict politicians’ heads lopped off, there is no Basquiat sloganizing, no roughly framed, invocation of chaos. My thoughts drifted to Nigeria’s constitutional situation and history. The police, the army, the judiciary, the press, the role of president. You can tilt at a society with established institutions more easily than one whose institutions are fragile. And yet. If you take to Nigerian twitter, you can hear the healthy, democratic clamour of criticism and judgement of govenments and corporations alike. Ankeli’s intervention is more metaphysical or symbolic than political; his work suggests an essential dignity in all human beings no matter their status or circumstances. And you can read that line (and the art) how you wish. None of the powers that be in Nigeria would have their hackles raised by seeing Ankeli’s mixed media art work on their walls: its political content is sufficiently ambiguous or latent to elude official opprobrium.

One aspect I loved to this work was the elusiveness of the human narrative. Step too close and you don’t see the figures within this painting. Step back three metres and they suddenly become apparent, two faces outlined using an African figurative/symbolic language: the narrow line for the nose, the small o for the mouth.

Zoom to extreme close-up and you see what might be interpreted as scarifications, blisterings, markings, repairs; the Japanese kintsugi tradition (of broken pottery repaired by gold) came to my mind as I looked this way.

There is an Africanity to the head shapes that reminds me in its silvery/bronze metallic sheen of female Ibo masks, of the wood masks of Kwele of Gabon, and the masks of the Guro of Ivory Coast. It got me thinking, as I looked, as to why my mind jumped to masks. The answer arrived that maybe painting is not an ancestral African art: to chance a sweeping statement, masks and sculpture are predominant historically in (West) African societies. From there I wondered how this Western form (painting) is adapted to African conditions, where it finds its home(s). Painting as far as I know is not used/adopted as part of ceremony or ritual nor has it become an aspect of court art, and it appears not to be present to any great extent as part of everyday life.

My mind drifted back. I was in Nigeria visiting relatives last year and, as you do, glanced at their walls as I went around. Lots of framed photographs of their children( the older ones where fortune had smiled on them, in mortar board and graduation gowns), older frames holding the elders of the family, sometimes in the black and white prints of gone times. Going around Manchester, UK, visiting friends, I have a similar experience. Photos of family adorn mantlepieces. Perhaps a few prints in Ikea frames make it up – New York, a lush tree, some Rothko-inspired blocks of colour. Occasionally there is a rarer print on a feature wall; in Black British houses, it might be something showing positive, strong, elegant black women with a rootsy yet modern African feel; or if the home is that of a loved-up couple, then a black romantic pairing under the wing of a swan or some other such gentle, protective, image, symbolically holding love in the house while the occupants go out to their nine to five. You get the gist. In both locations, no original art work. Why?

An original painting is expensive compared with a print. And paintings are often very large compared with the average household wall. Maybe they are made for public buildings such as art galleries, or for the very rich who have more wall space.

I remember in Lekki, a suburb of Lagos, Nigeria I visited an arthouse with a huge repository of contemporary African painting, with price tags in dollars that amounted to twice the prices of Chuck Gallery’s African art. The distinguishing beauty of that Lekki gallery was that the artists were often outside on those ubiquitous white plastic chairs, hanging out. (There was also a Wanted sign on the gallery’s front door, with a CCTV still of someone who had allegedly stolen a painting). You got a real sense that you were supporting the artists on the veranda, by buying a painting.

Of course, there is a value to paintings outside of whether they look good hung on a household wall. They allow alternative visions, such as Ankeli’s, to be shown. Artists are at the heart of thinking up new ideas about how we can live together in society; they produce a treasure trove of alternative ways of seeing the world and of being in the world: a Smash Glass In Emergency for different ways of living.

Ankeli is a fine artist, with an accomplished technique, a real Smash Glass In Emergency visual poet, and his reputation can only grow.